Andreas Kaju: how to really manage crises?

In a Covid-19 conference organized by Eesti Päevaleht, Andreas Kaju, founding partner of META, shared his personal experience; and the knowledge that plays a crucial role in crisis prevention, crisis management, and exit.

Oh, no one can predict such crises’, is the most common refrain. Such things happen once in a lifetime, once a century.

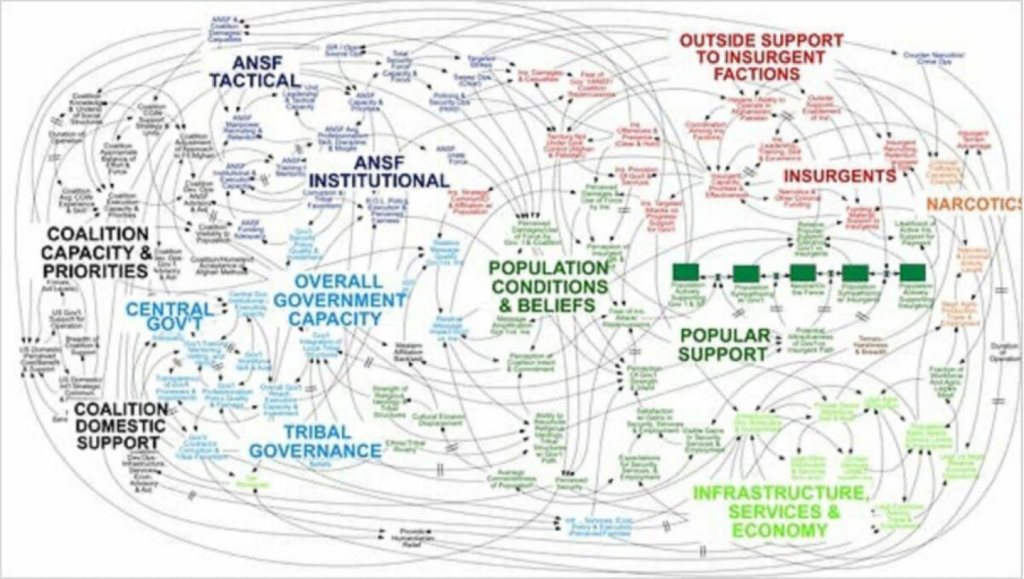

Indeed, none of the forecasting models available to corporate management, let alone risk managers, predicted with sufficient certainty either the Covid-19 pandemic

or the various government responses to it. Which, in turn, led to supply chain shock, restrictions on movement, a contraction in demand in some areas, and artificial restrictions in supply in others.

Life has shown that the risk management models of many big companies often tend to amplify rather than reduce risks, precisely because they try to envisage fantasy scenarios and anticipate complex problems rather than focus on practicing how to deal with the consequences of typical problems.

PRELIMINARY INFORMATION IS CRITICAL

Emergency preparedness does not arise when we predict extremely unlikely events and force companies to prepare for them. A very large part of the preparation for potential conflicts and military crises at the national level, and therefore, better preparation for deterrence and crisis prevention, is obtaining information.

Obtaining strategic information from public and non-public sources about our operating environment, including the competitive environment – if it is done systematically and in the long run – allows us to form a picture of the other parties’ principles, motivations, and considerations, which may influence their behavior in specific situations. In addition, this provides preliminary information about events or scenarios that may happen suddenly. At a time when military conflict is no longer preceded by a declaration of war by the other side – the most recent example of which was when the US declared war on Bulgaria, Romania and Hungary, members of the Axis, in the summer of 1942 – any adequate preliminary information about what will occur, is critical. You don’t want to find out about aggression the moment your enemy crosses the border.

This was also the main conclusion for me on the Georgian-Russian war of August 8, 2008, when I was working in the Ministry of Defense. I believe that over the following 12 years, Estonia’s efforts have largely been focused on improving strategic early warning. Accurate information about what will occur – even if not in terms of years, but rather months, weeks, days or sometimes mere hours – is extremely valuable for companies, just as it is for the state.

On a late winter afternoon in 2009, together with our partner Ott Lumi, we discovered that what we could do well, and what would add extra value to the clients of our emerging company, was the systematic obtainment and presentation of information to senior executives for strategic decisions, in a way that is understandable in their specific business context. In this way, we became the first company in Estonia to begin monitoring, reporting and, if necessary, managing companies’ political and other external risks as a professional service. As politics, public space, communication, reputation, and brands are inseparable from each other in terms of opportunities and risks, today we are a service agency, and a big one on the Estonian scale.

For 11 years, we have been systematically gathering and analyzing the necessary information about companies’ political risks and opportunities, and integrating it into our clients’ management models through our products and standardized processes, to make the most of it. When the Covid-19 crisis emerged, it became clear that the resilience of companies depends, unequivocally, on whether or not they had such management systems in place.

CRISIS COMMUNICATION: LESSON 1 – MENTAL READINESS

Photo: Miramax Films

Emergency preparedness does not arise when we predict extremely unlikely events and force companies to prepare for them.

However, it must be acknowledged that understanding this concept has greatly developed during the last decade. After the 2008 financial crisis

books by Nassim Taleb could be found on the desks of business leaders, the practical effect of which, if nothing else is understood, is to impress upon the reader the surprisingly frequent occurrence of events that are otherwise considered extreme. My own thinking has been significantly influenced by the game of poker. To put it very boldly – in order to become the Estonian champion in heads-up no limit poker in 2012 and play the game more seriously in the future – I had to first make a number of different concepts clear to myself. For example, the theory of probability and the perception of different probabilities, including the perception of both positive opportunities and negative risks, and the realization of actual probabilities.

High school math is enough to understand the basic mechanics of poker. We seem to understand what it means when the probability of something occurring in a certain situation is 98% or 2%. But a world-changing experience is seeing those cases with a 2% probability taking place repeatedly, within a day. When playing poker at multiple tables online, a couple of hours is enough to experience such seemingly unlikely statistical probabilities yourself – both the benefit and the damage. Without dwelling on this subject, I would like to say that the realization of unlikely scenarios depends on how often you put yourself in these situations and how prepared you are to reap the benefits of them, or are insured against them. But if you don’t remember anything else about this poker example and the theory of probability, then please just bear in mind this one thing – unlikely events are much more common in reality than you realize. Life has taught me that there are significant similarities between learning poker or learning chess, and good crisis management, but we will discuss this later.

An important difference between the randomness of skill games with an element of luck, as in poker, and extreme socioeconomic events, is that real life is less structured and much more chaotic than the randomness present in closed systems, such as in games with fixed rules.

We must prepare for the consequences.

This was, in fact, Taleb’s message – in order to prepare for crises and highly unlikely scenarios, it is not worth trying to predict them, because it is beyond your power, it is beyond anybody’s power. We must prepare for the consequences. What do we need to deal with the consequences?

There are a number of methodologies for managing external risks, including political risks, which have similar basic features. If we, in cooperation with the client, build the function of government relations in that client’s business organization, then we have a fundamentally similar goal to the Estonian Defense Forces – an efficient early warning of the risks that are beginning to materialize.

CRISIS COMMUNICATION: LESSON 2 – INFORMATION COLLECTION AND ANALYSIS

In technical terms, and in practice, this means a series of simple procedures and processes that, when routinely operated, ensure we generally know what is going on at any time. Easy, isn’t it?

What do we usually do? We define, in cooperation with the client, up to ten key topics/areas of their organization where new events would have the greatest impact on their business. For Delfi, for example, these could be changes in taxation, mail and home delivery, competition between digital companies, advertising regulations, freedom of expression and the protection of sources, and so on. When we have mapped the areas that could positively or negatively threaten the business, we then map the institutions and other actors that most influence these areas. The synthesis of these two approaches results in regular monitoring and surveillance products, which inform business decision makers according to their area of expertise, as well as what type and volume of information is the most important to their decision making. This includes decisions about preparing for the inevitable, but also conscious attempts to influence what is avoidable or possible. Such as lobbying campaigns.

Why am I talking about this during a Covid-19 Conference?

Well, what do you think – of two organizations, which was better able to regroup at the end of March, navigate between different Estonian institutions in April, find mitigation strategies, and perhaps have a say in the design of the necessary mitigation measures? Company A, who for the last seven years has carefully monitored, from week to week, every main development in its business areas and related institutions, and who has also actively managed its cooperative relations and two-way communication with stakeholders?; Or company B, who has not done so.

You know the answer yourself.

For ourselves, for META, the Coronavirus crisis meant supplementing existing monitoring and surveillance routines. We launched a special corona-monitoring report in our portfolio. Specifically structured reports that contained the information that most affected our client’s business, which we sent daily or, if necessary, up to several times a day. This real-life snapshot of the situation also enabled our clients to react immediately, at the right time, because they were ready and we were ready. Despite different interests, Astri and the Rocca al Mare Center were able to get onto the same page in terms of what the role of the state should be in mitigating the losses caused by the closures of shopping centers. As an Estonian company, Astri also left an indelible impression on me, because it was definitely one of those organizations whose values were clearly manifested in their crisis-handling behavior – such as how they immediately took part of their tenants’ burdens onto themselves. In the case of Rocca al Mare, we saw how top management, despite being far away from Estonia, very professionally trusted the Estonian management at the heart of the crisis, as the crisis progressed.

We got into the financial sector at the exact time,

it was necessary to design Kredex’s measures, and we were able to provide this process with precise data about what was really needed on the market. The fact that this was occasionally futile, was a moot point – at least it was due to passivity.

Yes, if mitigation measures or governmental policies sometimes take more of the interests of a particular group into account than another, it may seem unfair and sometimes it is. But sometimes the difference arises from a conscious, meaningful and systematic effort or the absence of such, not injustice.

- Identify the areas and topics that affect the business (where the potential impact of risks and opportunities is greatest)!

- Map all relevant actors to understand the impact of the vectors and power networks of these areas, as well as the interests of the parties, and their attitudes towards your interests!

- Develop a strategy for the ongoing involvement of stakeholders, depending on their relevance to developments in previous topics!

- From all this, an early warning system (the monitoring, collection, and analysis of information) emerges, which provides management with the practical information needed for decision-making (periodic, standardized reports).

CRISIS COMMUNICATION: LESSON 3 – MAKE THE FACTS CLEAR TO YOURSELF

In communication, you should always distinguish what you know for sure (almost 100%), what you do not yet know, and what you know in part or what is still being clarified.

There are other rules in a crisis. The principle being that the person in the middle of the crisis, the party responsible for it, must first make the facts clear to themselves, and make a very strict distinction between what is known for sure and what is not. Without further ado, it is obvious that our Coronavirus communicators sinned against this principle the most, and some may still be doing so. In an age when the media’s model of action is also based on the promotion of quick opinions, the prospect of discussing everything yourself, interpreting and guessing, is very attractive. But it is definitely wrong. Unlike, for example, the issue of gay marriage, where it is possible to exchange opinions on the basis of non-factual values, we do not want to get any such opinions from crisis managers on the Coronavirus, and all such opinions will be used against them later.

It is also a mistake to believe that some of the world’s most fascinating stories are centered on opinions and interpretations, and that this is the only way to send messages forward. Yes, we think in stories, we interpret the meaning of our own lives in stories, and we look at the world that way – but that does not mean that the world itself must always be presented in this way. A few days ago I read an old interview with the famous Jewish writer Isaac Bashevis Singer, in the Paris Review, that reminded me that Homer’s “The Iliad” and “The Odyssey” focused only on the transmission of facts.

If a writer tries to explain and construe, to psychologize too much, then his time is over before he starts. Imagine if Homer had explained the actions of his heroes in the context of ancient Greek philosophy and the psychology of his time! Nobody would read it. Fortunately, Homer only gave us the facts and the descriptions, and that is why these stories are still fresh today. ”Limit yourself to the facts” is a formula that helps you survive the first days of a crisis without making major mistakes.

CRISIS COMMUNICATION: LESSON 4 – ABOUT MISTAKES

In most cases, the facts you know for sure, should be disclosed as much as possible. This is contrary to what lawyers recommend. In communication, however, the problem is not the initial error, mistake or problem, but its subsequent concealment – and this is the opposite of the view of legal aid.

Of course, let me confirm, that I was not born yesterday.

There are some potential crises, related to some circumstances in which complete disclosure is simply not in the interests of the client and that’s just how it is. As this may ruin their personal life or business completely. My clear advice concerns cases where preventing the discloser of information is no longer realistic. In such case, the disclosure of the facts and circumstances is almost always the least bad choice in the overall conditions of war, speculation, and – let’s not forget – the opinions of various scammers.

Confidence and courage. Bad news comes out anyway, so at some point we probably won’t be able to come up with solutions ourselves. Yes, it’s a little embarrassing and we take risks, but we probably can’t escape it. If we wait and hope that it passes or drips by piece by piece, then we are definitely the losers. Especially if there is an internal leak behind negative media coverage. You always have to prepare for the worst.

This is even more evident in politics and the Covid-19 crisis. A typical situation is that cabinet discusses one or another restriction for five hours, and does not reach an agreement. Instead of talking publicly about the pros and cons of a solution, acknowledging the difficulty of reaching a decision and describing various considerations, nothing is said until one party is nervous and goes to brief the media that this or that kind of restriction will not come, because we are against it. With lot of speculation and unconfirmed data diffusion, people, consumers, and businesses alike, get nervous. People rush to the border areas to grab alcohol, or matches or flour.

Overall, it is important to understand that in crisis communication the so-called ‘negative program’ is much more important than a positive one. Instructions on how to do things well is less critical than instructions on what must not be done under any circumstances, and what should be avoided in any case.

Positive business literature is the playground owned by charlatans, says Taleb, and he is undoubtedly right. The shelves in our bookstores are also full of books about the accidental success of one-hit-wonders, which is somehow forged into a kind of rule. My chess and poker skills both started to improve quickly when I focused on avoiding my mistakes instead of winning every game or hand at any cost. Even grand masters in chess focus on avoiding mistakes in discussions with players of an ELO beginning with 1. Today’s culture of start-ups emphasizes somewhat the opposite – achieve the goal, do whatever it takes, even break things, it doesn’t matter. But, in general, companies have a certain lifespan, and those, who make big mistakes at some point, end in bankruptcy faster.

So, don’t lie, don’t hide, don’t make mistakes, don’t forget your employees, don’t forget your clients!

With strategies focused on avoiding mistakes, the banks that went bankrupt in the previous financial crisis, or even banks that lost their licenses in the last decade, would still be in business. Although their profitability might have been lower, because less risks would have been taken.

CRISIS COMMUNICATION: LESSON 5 – AUDIENCE AND PRIORITIES

Communication must always focus on the main audience – who is the main segment we need to inform? Too often I’ve seen that, in this area, communication teams should learn from their friends in the marketing teams. There needs to be a clearer understanding of who we are talking to, what their expectations and hopes are, and how we need to shape our messages in order to reach them to actually speak to them.

How much do you trust these people and institutions in relation to information about the coronavirus?

- Jüri Ratas an average of 44.9%

- Tanel Kiik an average of 38.8%

- Mart Helme an average of 3.8%

- Martin Helme an average of 6.4%

- Merike Jürilo an average of 21.2%

- Arkadi Popov 58.1%

- Irja Lutsar 43.3%

- your family doctor 43.7%

- newspapers 26.7%

- TV news 38.5%

Communication about the Coronavirus crisis showed this very clearly. In a situation where it depended on the words and actions of crisis managers, whether people felt safe, whether they could cope emotionally and at the same time be able to see an active role in managing the crisis themselves, some did better than others. Just for fun and a better understanding, our company commissioned a representative sample survey from Norstat to measure the reliability of various spokespersons in the Coronavirus crisis, and as expected, Jüri Ratas was the most reliable one. Why as expected? Because top politicians know their audience exceptionally well and speak in a way that may upset their rival’s voters, but their main audience is usually credible because they speak clearly, intelligibly, and simply.

Thinking about your audience also means that if you feel as though your organization needs to do something more than support your people, don’t overwhelm yourself with playbook ideas. Don’t go on social media to thank frontline workers for their efforts unless you’ve done something to help them – beyond sending your own staff to work from home.

If you want to help, go and ask what is needed. This is exactly the question we were facing with Coca-Cola, with whom I have been working with in the Baltic region for almost ten years now. They have a habit of contributing in both peaceful and difficult times, but instead of simply offering preconceived ideas and solutions, I grabbed the phone and called Maris Jesse, the Prime Minister’s Office, and North Estonia’s Regional Hospital management. And we very quickly reached a solution where our capabilities and very real need met – to acquire an additional mobile treatment unit for performing triage in other regions, as well as outside the main treatment building.

CRISIS COMMUNICATION: LESSON 6 – FIRST RAMPART: YOUR OWN EMPLOYEES

In a big organization, the company’s employees are the main ambassadors for the brand and its reputation. Hundreds and sometimes thousands of employees make more contacts than one mediocre press release or the rapidly disappearing Delfi news with 1,000 readers can ever achieve. Where possible, there should be accurate internal communication with a clear call to colleagues about what and how to communicate in your private channels to support the company and colleagues in difficult times.

In the Coronavirus crisis, organizations are firstly responsible for their own employees. To make them feel safe, to be the first to know how their company is doing, and what they can do to get out of this situation in the best possible way. A company that declares in public that it cares about the health of its customers during a crisis, but actually forces its employees to take unreasonable health risks in conditions of insufficient information, is not just disingenuous, but also inefficient. As the employees will very soon let the public know what is actually going

I have seen a number of examples of this during the crisis. Positive examples:

Swedbank and its internal manifestos, which I will discuss later;

Tele2’s front-line employees and Tele2’s decisions to protect their employees’ health and to close sooner rather than later, regardless of the actions of competitors.

Layoff and redundancy communications also gave a number of examples of otherwise very good companies – Starship vs. Veriff vs. Airbnb. The first went to the press with their shocking redundancy revelations, which were criticized by angry workers, while the other two, with their personal and carefully thought-out redundancy communications, won friends and sympathizers.

How did we do?

At the beginning of March, in Tallinn, I got well and truly sick. Since I have a family and children, I was completely isolated from the rest of the world. In late evenings I had the opportunity to walk quietly in the yard for an hour to maintain my sanity, and at the same time, a complete disinfection was done at home. So, personally, I wasn’t in top shape at the beginning of the emergency. But that is not a good excuse, of course.

Why an excuse? Because in retrospect, we could have worked even better with our team in the middle of the crisis. It took two or three weeks to take some important steps – to bring the whole team together to tell them what our plan was to cope, the situation with our portfolio, how we anticipate the impact of the crisis on our financial performance, and what it all means for us. Although we don’t know what will happen exactly, we need to focus on helping our distressed clients and not just count money as top importance, because the cash flow of some businesses – from dentistry to some retail shops – ran out. Our plan was not to reduce someone’s salary or send people away for economic reasons, but to cut back on company executives and other expenses, if necessary, in order to maintain the entire team, energy, and commitment. And to come out stronger than our competitors in the end. Today, we are one of a few agencies that did not lower wages, send people home, or apply for wage subsidies or other financial assistance from the state.

But more could have been done. I could have asked more about each individual, how exactly they were coping and feeling themselves. Because if I, one of the managers of the company, was worrying and working with my Excel models, then my colleagues who were lacking information even more, were certainly very worried. So, lessons for the teacher as well.

CRISIS COMMUNICATION: LESSON 7 – UNITY OF EFFORTS

The success of business communication has always depended on a concerted effort – whether all leaders are on board, and if the employees come along and participate or defend their employer at home or among friends. The need for cooperation and unity has become even more obvious in this nationwide health crisis. In a country where there are more registered taxi drivers than soldiers and police officers, it is not possible to force people to protect their own health and the health of their co-citizens. This requires cooperation.

Again, if we look at the recent past, this should be obvious..

Over the past decade, Estonian cyber history has been an important part of our reputation building, which added a new layer with Skype, Tiger Leap, and the e-government. Estonia’s cyber story, in turn, became possible thanks to the adventure of its eastern neighbor in the spring of 2007, where attempts were made to paralyze our IT infrastructure with coordinated DdoS attacks. Does anyone remember what led to the successful response from the national cybersecurity professionals and companies in IT infrastructure and essential services? It was the implementation of previously existing informal cooperation networks. Some may simply call it friendship, but it is certainly more than that – not in every environment and in every situation, are representatives of different institutions, private and public sectors, staff and professionals willing to work together at all costs – whether or not someone is honored for doing so with awards or bonuses. Which, mostly, are not given.

It requires a certain type of environment, a cooperation model from those who must set such models.

Why did the Health Board, in government press conferences, direct briefings for officials to tell all journalists different stories? Why did the government’s crisis committee draw posters and design crisis communications for hours? Maybe because they are the best in the field. But perhaps, it was because they did not trust their officials, the culture of informal cooperation is poor, no one wants to hear advice from the outside. All of which happens at a time when the government’s official crisis communication mechanism is the most professionally organized in the last 25 years, from a technical point of view.

Unity is the only thing that will save us in times of crisis. A crisis is devastating in conditions of uncertainty and it is nurtured in contradictions.

I’ve always wanted to own a consulting company that exists for growing and protecting my clients’ businesses, but I’ve also wanted for the people who work for us to feel that there’s always someone behind them who catches them, if needed, and who helps and supports, exclusively and always. Technology investor Ben Horowitz said in his first book at the beginning of the decade that he had one principle in assembling teams – no morons, no peacocks, no whingers. To be honest, this has also been a guiding principle for me in recruitment.

CRISIS COMMUNICATION: LESSON 8 – TRAINING, AND THESE DAMNED DETAILS

No, communication does not come first.

Communication is not the cause for crises, and rarely can communication be the sole solution. Although at a time when the number of active infections is five times higher than at the beginning of the spring emergency, it may seem that the crisis is something that is or is not in our heads, and is not necessarily related to any measurable, objective reality.

Crises are caused by rapid changes we have not been able to anticipate to an extent that would allow us to respond adequately in a way that would save our business.

Kriise põhjustavad kiired muutused, millega me pole olnud suutelised arvestama ulatuses, mis võimaldaks meil adekvaatselt reageerida viisil, mis meie ärisid säästaks.

Where did I get my illness at the beginning of the Coronavirus crisis?

In the last week of February I was away from Estonia for a day and a half on crisis management training at one of our clients, the world’s largest life sciences company, who focuses on taking care of human, animal and plant health. The training was exciting, although I’ve done simulation and scenario-based crisis exercises or wargaming before. Producing a scenario in real time or accelerated time and getting reactions and decisions from managers in a closed space, to which the scenarios react, is the best possible way to actually practice a crisis.

We learn from theory, as we do here today, but we also learn from experiential problem-solving, we learn from critical thinking, and we learn from reflective practice — reflecting on what we have done, drawing conclusions, and mending our behavior accordingly.

In general, our company does not provide this kind of training. There are many reasons for this, partly of an economic nature and partly of principle – we must always focus our advice and strength on our existing customers. But it is different with crisis communication. Although we direct these trainings primarily to our own customers. It is simply not possible to improve crisis management capacity in an organization in any other way than to repeatedly practice.

When did the Estonian Defense Forces turn from a ‘paper army’ to a powerful and capable force? When regular army reserve training began.

CRISIS COMMUNICATION: LESSON 8 – TRAINING, AND THESE DAMNED DETAILS

Leaders are different. Our 35 clients have hundreds of leaders with very different styles, and everyone has the opportunity to be successful. But in crises, some types definitely do better than others. Some people like to talk about peacetime leaders and wartime leaders. There are probably those who are very good at both.

But there are several valid elements of that otherwise trivial saying about not letting a good crisis go to waste.

A crisis is a change and a big crisis is a big change. No one knows exactly which windows and doors will survive in a crisis, nor which will be closed and which will be open when it is all over. Besides surviving, a crisis is also an opportunity to get better.

During this ongoing crisis I saw, and still see, many companies for whom the crisis enshrined their values within the organization. An even better opportunity is a crisis for companies that are themselves in a whirlwind of great change. With the help of a crisis, it possible to steer in an entirely new direction

One example of this is Swedbank.

Swedbank has certainly gone through hell and high water in recent years. And, of course, they still have a long way to go to restore public confidence. The entire management of the company has changed. Shareholders, who indirectly and directly make up the majority of the workforce, have suffered. The reputation of countries has also suffered. This, of course, has affected how the company sees the current Coronavirus crisis and deals with it. Swedbank’s experience in the 2008 financial crisis has also had its influence – how did they behave then. It is obvious that the Coronavirus crisis is a big challenge for Swedbank. Not simply because they have 1 million customers in Estonia, but also because the crisis is an opportunity to prove, first to yourself, that your values are more than just words on paper. That the cultural change that management seeks in the company can be seen in such a difficult moment, and not just for the public, but among the thousands of employees. Because this is what it depends on: on a company’s answer to how their private and corporate clients are treated at a time of crisis, when employees and employers are all struggling.

Thus, Swedbank made two manifestos, guidelines for its employees: “promises to companies” and “promises to people”, which set guidelines for all employees, and principles for approaching clients in this time of crisis. The manifesto explained to employees that the bank had not financed its clients too aggressively (without guarantees or self-financing) during the boom years. And that the differences in behavior of different banks during the current crisis are due to the differences in their behavior during economic growth. Swedbank is well capitalized due to its interim sustainability and was able to be flexible enough during the crisis to offer its clients payment holidays and, in justified cases, additional money. Swedbank’s initial task for employees in the crisis was to try to maintain and support the economic activity and coping of companies and people. The realization of loan guarantees for clients who had difficulties in paying their loans, had to be absolutely the last option in this crisis, and the most harmful. With the help of such guidelines, quick actions were taken. Payment holidays without surcharges and additional conditions, carefully continuing to issue investment loans, liquidity loans for maintaining the operation of companies, and assisting in launching state aid programs with both advice and actions. This all made an important difference, especially in contrast with several competitors, and influenced others to take a similar course.

But, in exactly the same way, employees also received honest guidelines for more complex tasks that needed a different approach: payment holidays cannot be granted to the interest component, the interest component of new loans can only be reduced with additional state guarantees, if these can be generated.

But above all, throughout the crisis, all communication must be transparent, honest and simple.

Because they wanted to be part of the solution this time, as the acceleration of recovery after a crisis depends on the agreements made during the crisis. In any case, I am really proud that during what was such a difficult crisis for so many, I have been able to work with a team including Olavi Lepa, Swedbank Estonia and, in fact, the whole group. And I have learned a lot in the process. In crises, the true values of a company are set in stone for a long time to come.

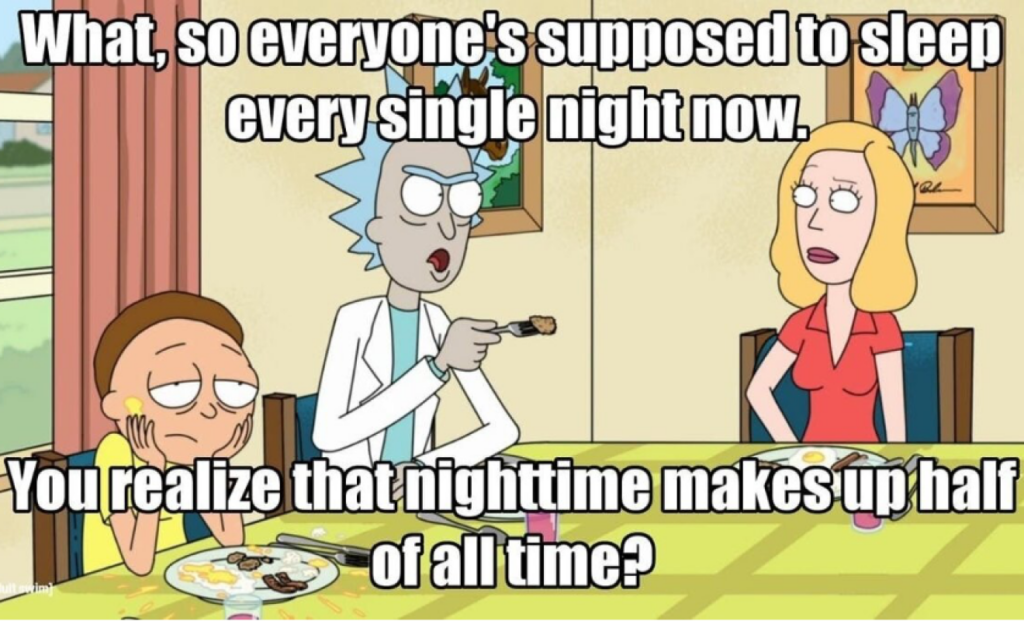

The very first lesson you learn from practicing a crisis is that every hour spent sleeping is worth your own weight in gold.

Finally, a small vignette about the underestimated nuances of crisis communication, of which I was reminded by a recent piece by Maris Vainre, a doctoral student at the University of Cambridge.

Namely, sleepless people do not manage crises. This is not a joke.

I have seen otherwise excellent leaders, moving sleeplessly around the city with residual symptoms of sleeplessness in the morning of the second day of a very difficult and deep crisis. First, believing “sleep is for the weak”, and second, the tensions and efforts to survive the first day of crisis made these middle-aged men desire to unload themselves.

Of course, they were useless afterwards.

The very first lesson you learn from practicing a crisis is that every hour spent sleeping is worth your own weight in gold. Crises and the accompanying tensions don’t last hours, they last days, weeks, and – as in the case of the Coronavirus pandemic – months or even years. Establishing work shifts, creating substitution plans, and living as healthily as possible during a crisis is the best investment to increase your chances of survival.

In a comment given this week, Aavo Kokk said something along the lines of ‘the crisis is good, you can make real decisions in it’. I believe him. I’ve been with him for two weeks, day and night, in crisis training, so to speak, and he obviously felt good in that environment. Like me, I like to think. But even he can’t escape sleep.

Thank you, it was a pleasure!